With trade policy unsettling markets at the start of the second Trump administration, it’s important to understand tariffs—what they are, how they work, and the bigger economic and political effects they bring. While they can help protect American businesses and bring in government revenue, they also come with downsides like higher costs for consumers and potential trade disputes.

What Are Tariffs and Who Pays them?

Tariffs are taxes imposed by a government on imported goods to protect domestic industries, generate revenue, or respond to unfair trade practices. While foreign exporters are affected, the actual cost is usually borne by U.S. importers, who pay the tariff before goods enter the country. These costs often get passed down to consumers through higher prices. In some cases, foreign manufacturers absorb part of the tariff to stay competitive. Additionally, tariffs can lead to retaliation from other countries, hurting U.S. exporters and businesses that rely on global trade. While they can benefit domestic industries, tariffs often result in higher consumer costs and economic tensions.

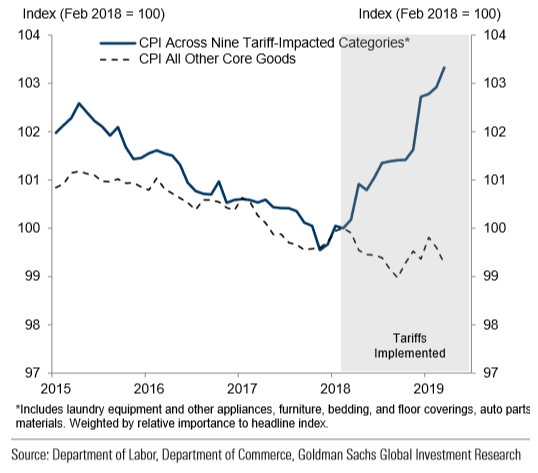

For instance, Goldman Sachs estimated that the tariffs introduced during the first Trump administration had a major impact on the cost of affected goods. With the current threat of even higher and broader tariffs, it’s likely that consumer prices will be significantly impacted.

The Evolution of Tariffs in the United States

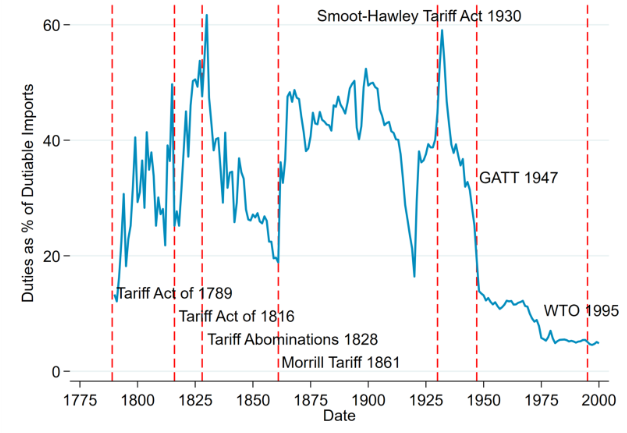

The U.S. has experienced several periods of fluctuating tariff rates, with rates rising and falling based on changing economic and political circumstances. In recent decades, the U.S. reached historically low tariff levels as the country moved toward more free-market policies. However, recent shifts in trade policy have led to a reversal, with higher tariffs being introduced as part of a renewed focus on protecting American industries and addressing trade imbalances.

The Early U.S. and Protectionism (1789–1860s)

One of the first legislative actions by the U.S. Congress was the Tariff Act of 1789, which aimed primarily at generating revenue for the young government. As the nation industrialized, tariffs were increasingly used to protect domestic manufacturing from foreign competition. The Tariff of 1816 was one of the first major protectionist tariffs, particularly benefiting Northern industries. However, this protectionist stance led to political conflicts from Southern opposition to high tariffs that harmed agricultural exports.

The Civil War and the Gilded Age (1860s–1900s)

During the Civil War, the U.S. government increased tariffs under the Morrill Tariff (1861) to fund military expenses. In the post-war period, high tariffs remained in place, fostering the rapid growth of key industries such as steel and textiles. However, as seen with the McKinley Tariff of 1890, excessive protectionism sometimes led to public backlash and economic instability.

Early 20th Century and the Great Depression (1900–1930s)

The Underwood Tariff of 1913 marked a shift toward lower trade barriers, reflecting progressive-era ideals of increased global economic participation. However, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, enacted during the Great Depression, reversed this trend by imposing high tariffs to protect American jobs. This move backfired, triggering retaliatory tariffs from other nations and exacerbating the global economic downturn.

Post-World War II and the Free Trade Era (1940s–1990s)

Following World War II, the U.S. led efforts to promote free trade through agreements such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947. The Trade Expansion Act of 1962 empowered the president to negotiate tariff reductions, and by 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was established, eliminating most tariffs between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. This era saw a dramatic shift away from protectionism toward globalization.

The 21st Century: Trade Wars and Globalization (2000–Present)

In the 21st century, tariff policies have undergone significant reevaluation, particularly in relation to trade with China. China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 led to a surge in imports, raising concerns about domestic job losses and manufacturing decline. During the first Trump administration, tariffs were imposed on Chinese goods, steel, and aluminum, triggering a trade war. The Biden administration maintained some of these tariffs while prioritizing other strategic trade alliances, highlighting the ongoing debate over balancing free trade with domestic economic security. In the second Trump administration, this trend has intensified, with the president imposing and threatening steep tariffs on both adversaries and allies, further reshaping global trade dynamics.

Do Trade Imbalances Matter?

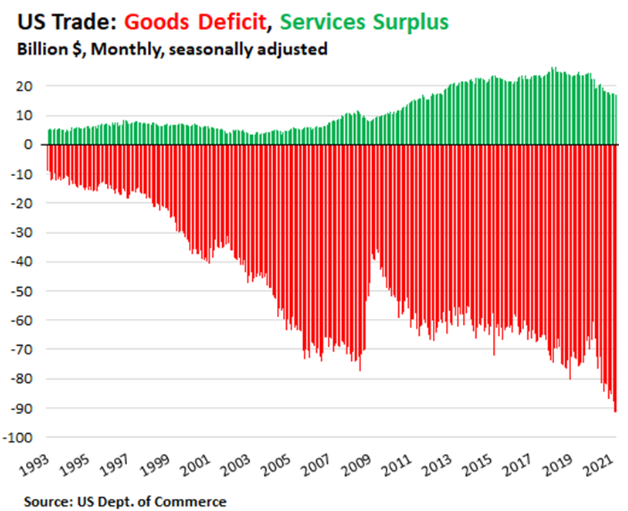

Trade imbalances can have significant effects depending on the context. A trade deficit, where imports exceed exports, can lead to rising debt, currency depreciation, and harm to domestic industries due to competition from cheaper foreign goods. Conversely, a trade surplus may indicate a strong export sector, but if too large, it can appreciate the currency, making exports more expensive and reducing demand.

Despite these concerns, trade imbalances aren’t inherently harmful. The key is whether they can be sustained without leading to long-term debt, currency instability, or weakening industries. For example, the U.S. has shifted from a goods-based economy to one focused on high-value services such as chip design, rather than manufacturing, while still maintaining its global economic leadership. Although it’s true that government debt as a percentage of GDP has surged in recent years, this is primarily due to emergency spending during the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID pandemic, not the U.S. trade deficit.

Conclusion

Tariffs have long played a significant role in shaping U.S. economic policy, reflecting the nation’s shifting priorities and political landscape. Tariffs, when used judiciously, can be a powerful tool in trade negotiations, encouraging fair competition and protecting key domestic industries. However, history has shown that their unintended consequences—such as supply chain disruptions, inflationary pressures, and retaliatory measures from trade partners—can often overshadow their intended benefits. The increased costs borne by consumers and businesses may offset any short-term gains for domestic producers, creating economic inefficiencies rather than sustainable growth.

With so much uncertainty, we stick to the fundamentals of long-term investing: staying diversified and making disciplined decisions. By focusing on the long-term, we can ride out market ups and downs with confidence, keeping portfolios positioned for lasting success.